Youth and War

R

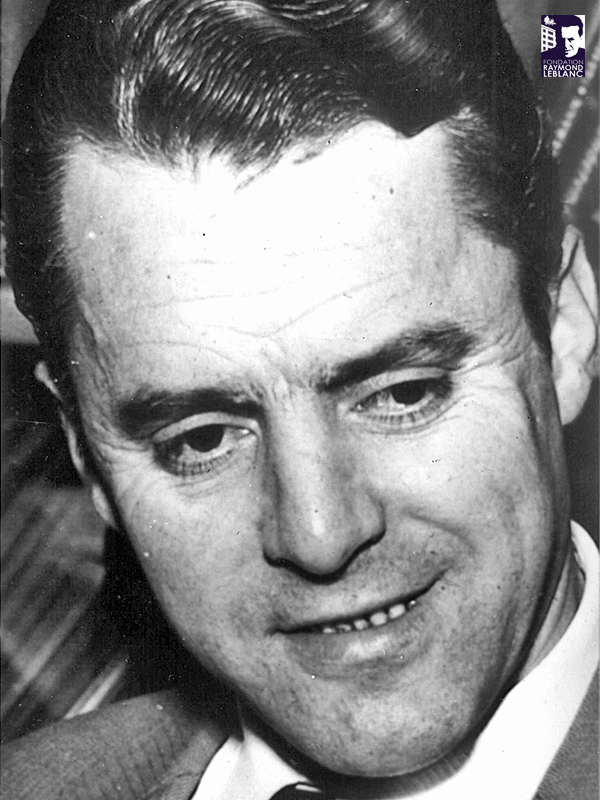

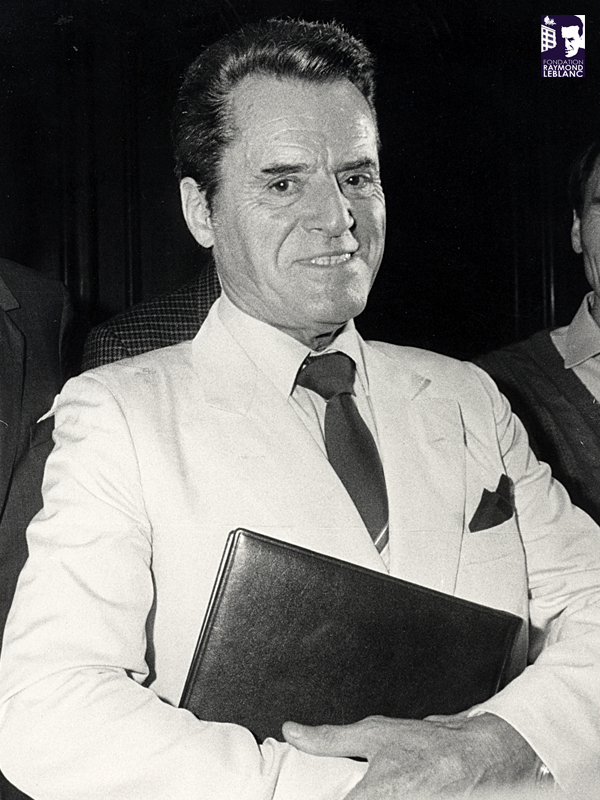

aymond Leblanc was born on May 22, 1915 in Longlier, near Neufchâteau, in the Belgian Ardennes.

As a young man, he began a career within the Civil Service as a Customs Inspector. The War in 1940-45, however, altered his destiny. As a reserve officer in 1942, he published his first work dedicated to the war, “Dés pipés – Journal d’un Chasseur Ardennais.” At the same time, he joined the Resistance.

In the days following World War II, Raymond Leblanc decided to go into business. He partnered with two friends who were as passionate about publishing as he was: André Sinave and

Debaty.

In December 1944, the three set up a small publishing house called “Yes.” The young company, which had only about ten contributors, settled in Brussels where it occupied three buildings at 55 rue du Lombard, near the famous Grand-Place. This address influenced the name of a new company established later, within the same building: “Les Éditions du Lombard.” Two periodicals originated from these first offices: the “Cœur” collection, subtitled “le roman d’amour du jeudi,” a weekly collection of complete love stories, and “Ciné-Sélection,” a cinematic news magazine.

Raymond Leblanc speaks about it (2005 – FR) : Willy Vandersteen

The launch of the Tintin magazine

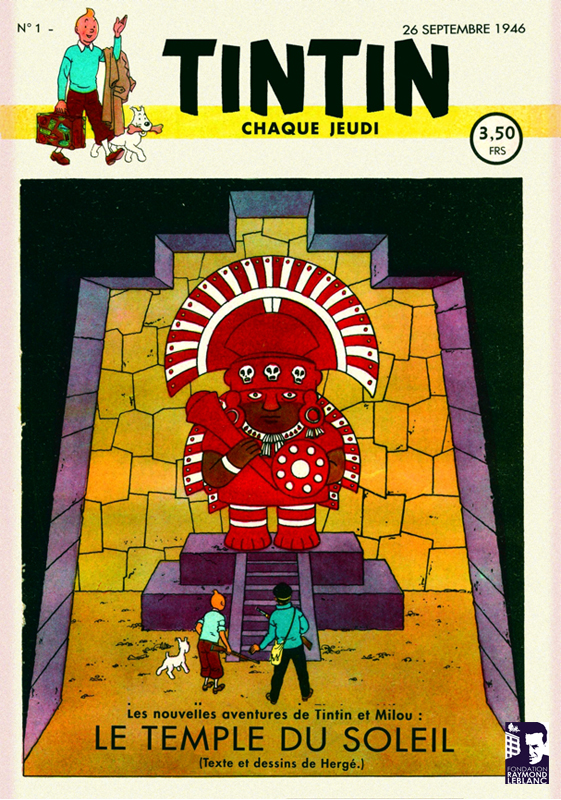

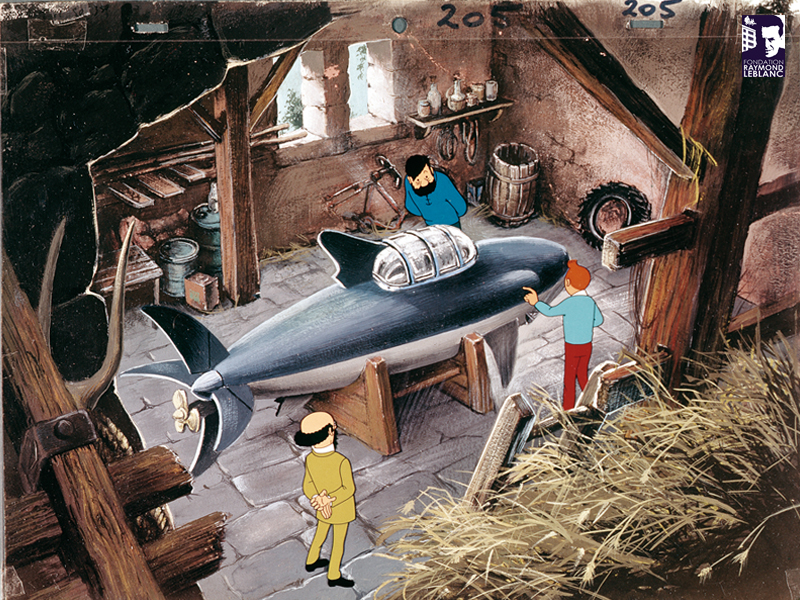

In 1945, Raymond Leblanc tried, with A. Sinave, A. Debaty and G. Lallemand, to persuade Hergé to create a periodical for young people, called “Tintin” magazine. Hergé agreed to it. Created in 1929 and already popularized by twelve albums published through Les éditions du Petit-Vingtième and then Casterman, the “little reporter” so became the headliner of a 12-page weekly comic strip magazine.

Hergé, artistic director, rounded out the team at “Tintin” magazine with three friends: Edgar P. Jacobs, Jacques Laudy and Paul Cuvelier. The four talented writers demonstrated tremendous energy.

As Hergé meticulously carried on the adventures of Tintin and Milou in “Prisoners of the Sun,” Edgar Pierre Jacobs innovated with “The Secret of the Swordfish”, introducing Blake and Mortimer, future stars of the comic strip .

With the makings of a great cartoonist, the young P. Cuvelier created “Corentin Feldoë’s extraordinary odyssey.” Little known to the mainstream public, J. Laudy illustrated with poetry and romanticism, “The Legend of the Four Aymon Brothers.”

On September 26, 1946, “Tintin” magazine and its Dutch counterpart “Kuifje” appeared in kiosks and bookstores throughout Belgium. Several days later, nearly all of the 60,000 copies had been sold.

In April 1947, the weekly “Tintin” magazine became “the magazine for kids ages 7 to 77.”

In 1948, Raymond Leblanc convinced the young Parisian editor Georges Dargaud to co-edit a French version of the weekly magazine. For more then 350,000 French youths, reading “Tintin” magazine became a treasured weekly activity.

Raymond Leblanc speaks about it (2005 – FR) : La ligne claire

Business development

In 1950, the success of the magazine prompted Raymond Leblanc to begin publishing albums of the comic strips that had been popularized by the weekly magazine.

The first two volumes appearing under the Éditions du Lombard label were signed Edgar Pierre Jacobs (Blake and Mortimer – “Le Secret de l’Espadon” T.1) and Paul Cuvelier (“Les Extraordinaires Aventures de Corentin”). This initiative ushered in the publication of approximately 1,500 titles, of which more than 800 still account for the nearly ten large collections of the current catalog.

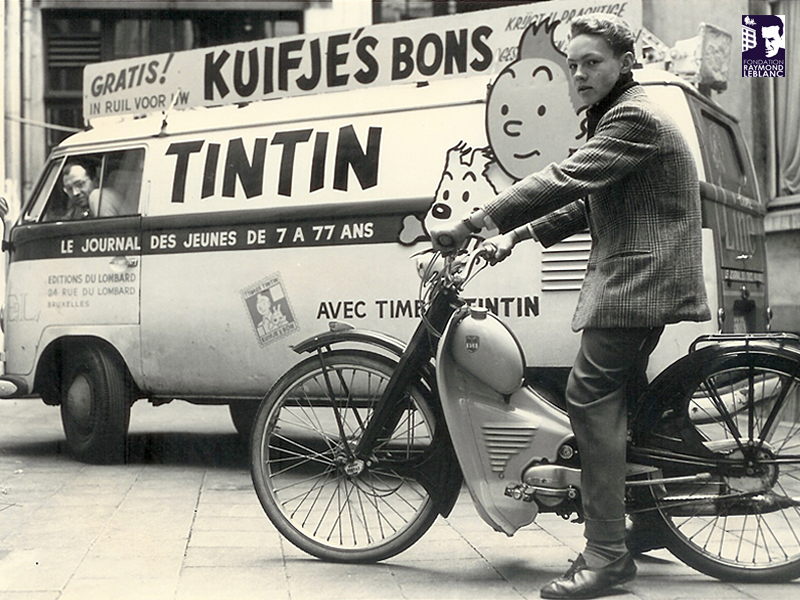

In December 1950, Raymond Leblanc decided to reward the magazine’s readers by creating loyalty points to save and collect, called “Timbres Tintin” (“Tintin Stamps”) ou “Kuifje’s bon.” These stamps appeared in the Belgian magazine in January 1951. French readers had to wait until 1952 for their version of the stamps, called “Chèques Tintin” (“Tintin Checks”) for legal reasons. In exchange for a given number of points, these coupons could be traded for various prizes (a genius idea): puzzles, portfolios, and also the

chromolitho books “Voir et Savoir” – illustrated by the Hergé Studios -, goose games, etc.

In light of this craze, food producers caught onto the concept of the “Tintin Stamps” by putting bonus stamps on their packaging. This unexpected success required the company to hire about twenty new employees to manage a department dedicated to the stamps. Approximately 200 million “Tintin Stamps” circulated each year in Belgium.

Raymond Leblanc understood the mutual interest in making readers loyal and found the means by which to make it successful for his business.

Still in 1950, having overflowed its 55 rue du Lombard location, the company expanded into a larger building located at number 24 of the same street, first on one level, and then on two levels in 1952. The first “Magasin Tintin” (“Tintin Store”) opened on the ground floor.

In 1953, les Éditions du Lombard published “Junior,” the children’s supplement of the review “Chez Nous.” Within its pages was born, among others, the series “Chick Bill” by Tibet.

Raymond Leblanc speaks about it (2005 – FR) : Le journal Tintin et Franquin

Publiart

In July 1954, Raymond Leblanc created the advertising agency “Publiart,” which he entrusted to the direction of Guy Dessicy.

For the first time in Belgium, an advertising company used comic strip characters. The agency had major clients, such as Côte d’Or and Coca-Cola. This agency later created the famous character of Walibi The Kangaroo, a popular Belgian amusement park.

Belvision

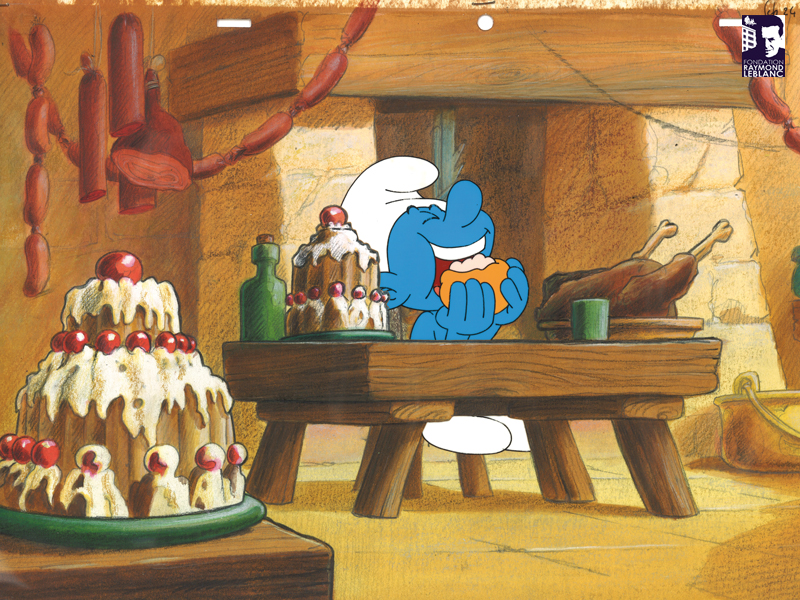

On December 11, 1954, the “Belvision” studios were born, which animate comic strip characters by hand for television. Later, the studios were equipped with a more sophisticated material and assembled a staff that was capable of producing short and full-length animated films for the big screen, like “Pinocchio in Outer Space”, a Belgian-American co-production, and even “Astérix the Gaul,” “Asterix and Cleopatra,”Tintin and the Temple of the Sun,” “Lucky Luke – Daisy Town,”

“Tintin and the Lake of Sharks,” “Gulliver’s Travels,” “The Smurfs and the Magic Flute,” etc. Belvision became one of the largest studios producing full-length films in Europe, as well as promotional films and documentaries starring comic strip characters from “Tintin” magazine. Created by rare European animation specialists, Belvision’s productions met worldwide success. They were called the “European Hollywood of animation.”

Raymond Leblanc speaks about it (2005 – FR) : Le Slogan du journal Tintin

On March 11, 1955, still associated with Georges Dargaud, Raymond Leblanc launched “Line,” a weekly magazine subtitled “the magazine for stylish girls.” as a version of “Tintin” magazine for female readers.

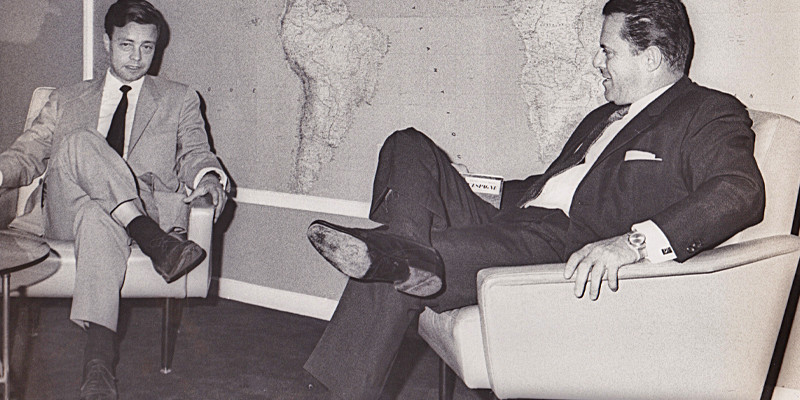

On September 13, 1958, thanks to the tremendous success of “Tintin” magazine and “Tintin Stamps,” Editions du Lombard, Publiart and Belvision, who employed some 100 people at the time, left Lombard Street for a new building designed by Raymond Leblanc on avenue P.-H. Spaak, near Gare du Midi. Paul-Henri Spaak, himself, officially inaugurated “his” Avenue and “Tintin Building.”

In 1962, after being well-known in Belgium, Raymond Leblanc, with Georges Dargaud, became the co-editor of the weekly magazine

“Pilote,” specially created by René Goscinny, Albert Uderzo and Jean-Michel Charlier.

In December 1963, bought out by Daniel Filipacchi, the weekly magazine “Line” gave up its place to “Mademoiselle Age Tendre,” a magazine for “young girls in the wind.” Lombard maintained the Belgian version of it.

When asked about the great success of his company and its ability to discover talent, Raymond Leblanc quotes the famous American phrase: “There are no successful businesses. There are only successful people.”

Clever businessman and visionary, Raymond Leblanc is unquestionably among those who, with Charles Dupuis, Casterman and Georges Dargaud, have contributed so much, such that the Comic Strip is now

recognized as the 9th Art.

At the end of 1986, Raymond Leblanc gave up Éditions du Lombard to the French-Belgian group Média-Participations, to whom he later entrusted its direction.

On November 29, 1988, the last issue of “Tintin” magazine went to press. “Kuifje”, the Dutch version, continued still until June 26, 1993.

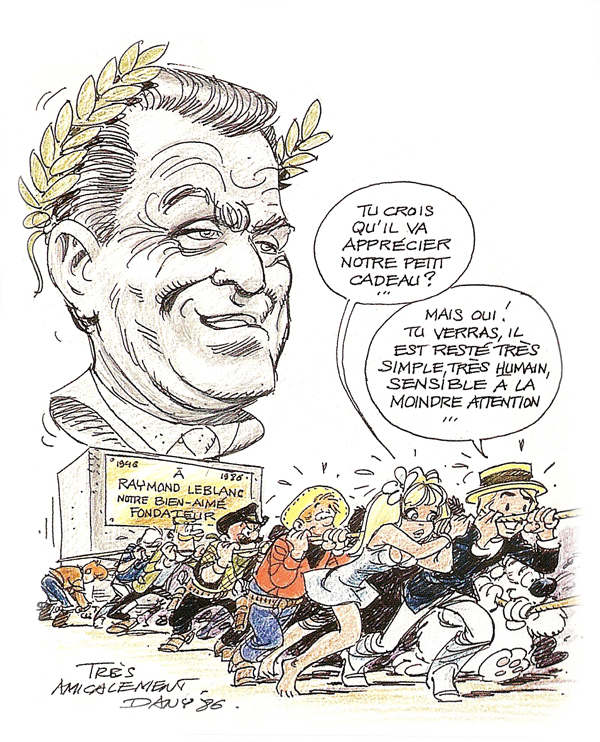

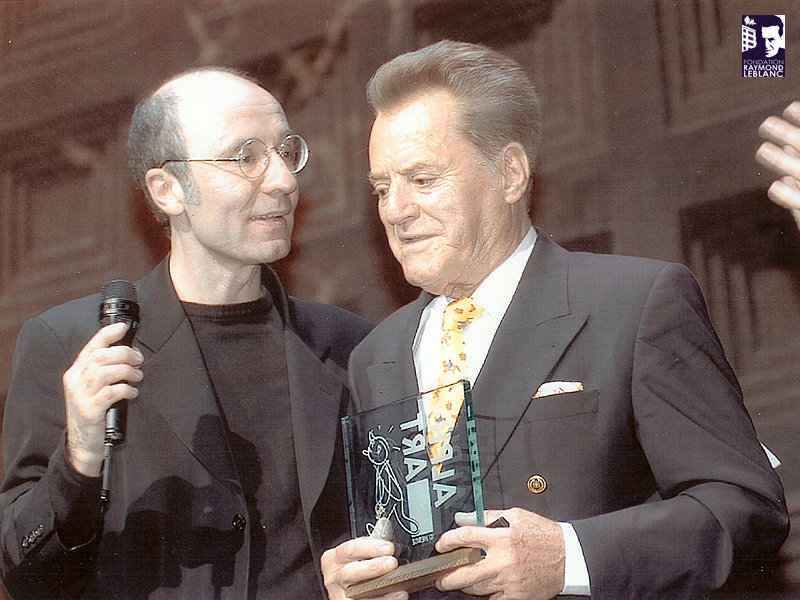

In 2003, during the 30th International Comics Festival at Angoulême, the profession paid homage to Raymond Leblanc by awarding him the first honorary Alph-Art given to an editor.

The Honorary President of Éditions du Lombard, Raymond Leblanc regularly used to visit in the years 2000 his his office on the 8th floor of the famous building on avenue Paul-Henri Spaak, beneath the

famous giant sign featuring Tintin and Milou.

On September 26, 2006, Éditions du Lombard celebrated the 60th anniversary of its founding and the creation of “Tintin” magazine. For this occasion, various public displays were organized.

Meanwhile, the memoirs of Raymond Leblanc, composed by Jacques Pessis and titled: “Raymond Leblanc, Le Magicien de Nos Enfances – La Grande Aventure Du Journal Tintin” (“Raymond Leblanc, Magician of Our Childhood – The Great Adventure of Tintin Magazine”) have appeared with the Éditions de Fallois.

Raymond Leblanc passed away on the 21st of March 2008 at the age of 92.